Friday, 24 April 2015

Skirr Cottage Diary

A quick trip down into the Goyt Valley after work gave me three new year migrant ticks and quite a few more regular species. First bird was a lovely female redstart getting some aggression from a robin. The usual Canada geese and cormorants on river end of the reservoir and then the first year sight of a common sandpiper which was a bonus. A walk towards the Riverside Walk produced my first year male pied flycatcher. On the way back along the old coach track to the car park I spotted a pair of pied flycatchers flitting about in a still leafless oak on which was placed a nestbox. Other birds spotted on my short trip were a pair of ravens, kestrels, long-tailed tits, blue and great tits, nuthatch, buzzard, sparrowhawk, goldfinch and great spotted woodpecker. Hoping for tree pipit and cuckoo but saw nor heard either just yet.

Sunday, 19 April 2015

Skirr Cottage Diary.

Gardening all day

today in the top garden. A lot of action in the back field which the garden

looks over. During the morning two hares were spotted leaping the field wall

and enter the back field. They proceeded to play a game of chase then

eventually settled down to preen and nibble herbs in the grass. After about

half an hour an irate cock pheasant suddenly ran across the field and with

much noise flew at the hares driving them reluctantly out of the field. He then

strutted about paying a hen pheasant much attention.

Later a female

sparrowhawk swept in and took a starling which she took to the edge of the

trees by and proceeded to pluck. The jays are still about and often visit the

bird table and are great to watch. Two buzzards were seen circling nearby and I

am wondering if they may nest up on the edge in the woods.

Saturday, 11 April 2015

Great nature writers series: Mark Cocker.

Great nature writer series. Mark Cocker: 'Crow Country'.

Crow Country: A Meditation on Birds, Landscape and Nature

by Mark Cocker

by Mark Cocker

The Brits have always loved birds, but rarely so much or so obviously as now. Several newspapers - including this one - have recently published handy identification charts; an amateur guide has appeared in the bestseller lists; TV twitchers have taken to promoting seasonal garden watches; the RSPB is flourishing. Why the sudden surge of interest? It's partly a response to our increasingly urbanised lives: wings over a city, let alone across the countryside, remind us of ancient freedoms and connections. And it's partly a proof of larger anxieties about the environment as a whole. Wherever we train our binoculars, our focus is sharpened by a melancholy sense of foreboding. If even that most commonplace small brown one - the sparrow - is disappearing from some areas, what does that mean for blackbirds and thrushes, wrens and robins? What familiar emblems of home will we be left with?

Crows, probably: they have always been great survivors. But crows have never inspired the same easy affection as most other birds. Farmers have regard them as a menace, shooting them and nailing their bodies to barn doors, or ransacking bottom drawers to make scarecrows. Professional ornithologists - with a few honourable exceptions - have preferred to concentrate on rarer or more beautiful species. Amateurs have swivelled away with faint shudders of revulsion: crows, after all, are faintly disgusting creatures, with their pickaxe beaks and big, scrawny feet. No matter how often we see them harmlessly bouncing across open pasture or ragging through breezy skies, in our mind's eye we associate them with the aftermath of battles. We imagine them tearing at flesh and uttering harsh cries of predatory triumph.

It's a sign of the times, and also of his eloquence as a naturalist, that Mark Cocker is able to overcome these prejudices and get his new book airborne. Writing with the same sort of passion that propels J A Baker's great serenade The Peregrine (1967), he makes a ubiquitous bird seem special. His prose may not reach the same heights as Baker's rapturous ascents, his sense of communion may not measure the same devastating weight of mortality, but his ability to convey the power of an obsession is just as great, and his eye is as bright.

Cocker is also more of a scientist than Baker - more expert and more simply informative. This is just as well, since although crows are widespread they are mightily misunderstood, often to the extent of being confused with rooks and other corvids. (The easiest way to distinguish crows from rooks at a distance is to count their numbers: a crow "passes its life as one of a pair isolated from neighbours by a fierce territoriality . . . Rooks, by contrast, live, feed, sleep, fly, display, roost, fall sick and die in the presence of their own kind". Hence the old East Anglian adage "When tha's a rook, tha's a crow; and when tha's crows, tha's rooks".)

Cocker's title suggests a narrow beam of attention. In fact his book has interesting things to say about all seven breeding representatives of the corvid family that exist in Britain, and celebrates rooks in particular. His opening chapter lets us understand why. Watching "a long ellipse" of several thousand rooks and jackdaws head for their evening roost, he is lifted into ecstatic delight - entranced not just by the mass of the birds themselves, but by their power to "act like ink-blot tests drawing images out of [his] unconscious". In other words, the flocks plunge him deeply into himself while seeming marvellously other than himself, compelling him to ask questions about how language can contain a sight so amazing, and also to wonder how the birds articulate elements in his deep un- or sub-conscious.

This response, which is at once personal and generic, forms the foundation of everything that follows: Crow Country is a slice of autobiography, as well as a bird book. Once the opening roost-scene has settled into a cacophonous dusk, Cocker turns to look at his own recent past, describing how he and his family moved from inner-city Norwich to make a home in the flat country of the nearby Yare valley. The change is presented as an act of migration which is at once bird-like (because it is driven by instinct) and falteringly human (because the new house, at least to start with, leaves him feeling disoriented). As he begins to acclimatise, he finds that rook-watching charges "many of the things I had once overlooked or taken for granted . . . with fresh power and importance". The birds, he says, are "at the heart of my relationship with the Yare . . . my route into the landscape and my rationale for its exploration".

At first it seems that Cocker will use this sense of induction as the launch-pad for a strictly systematic account of the place and its birds. His opening chapters contain necessary facts about identification and habitat, they provide descriptions of "special encounters" which reinforce his belief that "natural history can serve as a metaphor for life itself", and they give accurate "reckonings" of numbers and behaviour patterns. They also summarise the main features of his watery and elusive landscape - the strange separations created by the river that bisects it, and the trees of Buckenham Carrs where his rooks congregate.

But as his book develops, it refuses to fly as its subject is supposed to do - in a straight line - preferring to ride on thermals of enthusiasm. One moment he is darting off to Dumfriesshire to search for one of the largest roosts recorded in these islands, the next he is back by the Yare ruminating on the associations of the birds' calls, the next he is pondering the significance of crows' "weddings" and "parliaments", the next he is brooding on "the dynamic relationship between rookery and roost". There would be a danger of these wanderings becoming confusing, were it not for the fact that they all partake of the same spirit of passionate inquiry. Cocker wants to map the "where" of his birds (and in so doing adds significantly to our understanding of the natural history of the region) and also to comprehend the "why". Why do rooks gather together? Is it for shelter, for the sharing of information? How do they understand the notion of family?

Cocker is as good a naturalist as he is prose-poet - which means Crow Country has authority as well as charm. It is also a kind of echo chamber, full of references to previous rook-fanciers whose observations blend with his own, creating a sense of "deep vistas" that open into a "vanished past". He quotes Thomas Browne and Andrew Young, John Clare and Edward Thomas - a small anthology, in fact, of kindred spirits. Puzzlingly, there's no mention of Ted Hughes, whose Crow poems feed so greedily - and famously - on the violent mythic associations of the birds. Did Cocker feel that to mention Hughes (to whom he refers admiringly in Birds Britannica) would be to undermine his efforts to rehabilitate crows? Possibly - but the omission is a pity. Crows may be a great deal smarter than most people think, and more likeably fascinating, but there's no denying that their claim on our interest has a great deal to do with what is opportunistic and ominous about them. Hughes realised this, and the force of his poems depends on it. Cocker's corvids are more nearly amiable; the beauty of their wheelings and flockings might take him out of himself, but at the end of each day they reliably lead him home.

By Andrew Motion poet laureate.

Tuesday, 7 April 2015

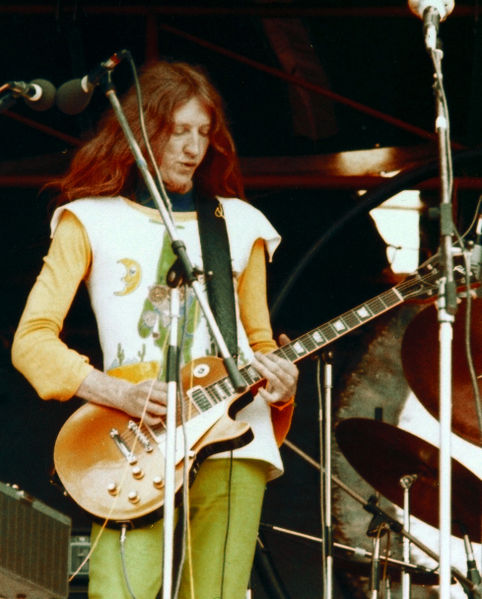

Daevid Allen: Gong.

DAEVID ALLEN Tribute.

If anybody could be said to have defined the spirit of globalist, free-thinking hippiedom, it was Daevid Allen, who has died of cancer aged 77. As a musician, he was best known as a founder member of Soft Machine and for his work with the cosmic acid-collagists Gong, but Allen was also a poet, philosopher and performance artist. After spending years in England, France and Majorca, he moved back to his native Australia in 1981, where he worked on his poetry while becoming involved in numerous electronic and improvisatory musical projects.

His early influence on Soft Machine helped propel the group beyond their bluesy roots into a daring experimentalism, where free-form jazz and the avant garde collided. As guitarist and singer with Gong, Allen helped forge a kaleidoscopic sonic palette capable of expressing the most whimsical imaginings, which would influence later generations of rave and electronic musicians.

Born in Melbourne, son of Walter and Helen, Allen was working in a Melbourne bookshop when he discovered beat writers such as Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. He became involved with the nascent Australian underground movement, known as the Push, of which he said: “That was such a great name. It meant that we were always there, pushing ahead.”

However, like his near-contemporaries Barry Humphries and Germaine Greer, Allen realised that Australia at the turn of the 60s was not at the centre of the counterculture revolution. “I left because of the heavy materialistic aspect and a couple of friends suicided at the same time,” he recalled. “I just got this bug in my head that I should split.” He took a ship to Greece and ended up in Paris, where he stayed at the Beat hotel, in the very room previously occupied by Ginsberg and his partner Peter Orlovsky. Also in Paris, Allen met the then unknown composer Terry Riley and helped him experiment with tape loops.

In 1961, Allen travelled to London, and his advertisement for lodgings in the New Statesman brought a reply from the BBC journalist Honor Wyatt, inviting him to stay with her family in Kent. The Wyatts’ son, Robert, was another musical star in the making. “I found Robert, who was 15 at the time and a real prodigy,” said Allen. “He was a real influence to me ... I’d just discovered [the avant garde saxophonist] Ornette Coleman and this whole period revolutionised me.” Allen and Wyatt made some of their first music together as the short-lived Daevid Allen Trio, with Hugh Hopper on bass. Allen then returned to the houseboat he kept at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris, where he lived with his partner, the poet Gilli Smyth. He invited Wyatt and Hopper to visit, treating them to a mind-expanding diet of LSD and mescaline (Allen being a conspicuously early adopter of psychedelics) and tapes of his own experimental music.

Advertisement

Allen returned to England in 1966 and resumed playing music with Wyatt and a shifting roster of Kent-based musicians. The group originally known as the Wilde Flowers morphed into Soft Machine, featuring Allen and Wyatt alongside Kevin Ayers and Mike Ratledge. They became rising stars of the burgeoning British underground scene, and signed a management deal with Chas Chandler and Mike Jeffries, who handled the Animals and Jimi Hendrix. Summer dates on the Côte d’Azur made Soft Machine a succes d’estime in France, particularly after they played at the producer Eddie Barclay’s Nuit Psychédélique. But when they returned to the UK Allen was denied entry because his passport and visa had expired.

Back in Paris, he and Smyth formed Gong, with Ziska Baum on vocals and Loren Standlee on flute. However, their progress was interrupted by the violent demonstrations of 1968, in which Allen participated, handing out teddy bears to the riot police in fine peacenik style. Smyth and Allen decamped to the isolated village of Deya in Majorca, also home to the poet Robert Graves. Legend has it that it was in a cave on Graves’s property that they found the saxophonist Didier Malherbe, whom they recruited to Gong.

They returned to Paris after being invited to record the soundtrack to the movie Continental Circus, and signed a deal with BYG records, which released Gong’s debut album, Magick Brother/Mystic Sister, in 1970, with Camembert Electrique and Allen’s solo album Banana Moon following in 1971. In 1973 Gong signed to Virgin, after BYG went bankrupt while Gong were recording at Virgin’s Manor studios. The first Virgin release was Flying Teapot (1973), a smorgasbord of jazzy rhythms, nursery-rhyme melodies and inventive electronica, and its follow-ups Angel’s Egg (1973) and You (1974) completed Gong’s so-called Radio Gnome Trilogy, featuring the concept of an imaginary planet called Gong.

The group’s capabilities had been greatly enhanced by the arrival of the guitarist Steve Hillage, but in 1975 he suddenly found himself left in charge of the band when Allen quit, having refused to go on stage for a gig in Cheltenham because he believed he was being held back by a force field.

Allen and Smyth retreated to Deya, Allen commenting: “I’ve spent far too long – in and out of Gong – blowing it in various ways, so I’ve come here to work on it.” He recorded the solo albums Good Morning (1976), Now Is the Happiest Time of Your Life (1977) and N’Existe Pas! (1979). In May 1977, Gong played a reunion gig in Paris, and Allen and Smyth also performed as Planet Gong. A 1980 collaboration with Bill Laswell was dubbed New York Gong and produced the album About Time.

By now Smyth and Allen had separated, and in 1981 Allen returned to Australia. He had had two sons, Orlando and Taliesyn, with Smyth, and now had a third, Toby, with his new partner, Maggie Brown. They moved to Byron Bay, 100 miles south of Brisbane, though Allen and Brown lived separately. Smyth had married the musician and producer Harry Williamson in the UK, the pair of them having formed Mother Gong, and they moved to Australia in 1982.

In 1988 Allen was back in the UK with a new partner, Wandana Turiya (with whom he later had a fourth son, Ynis), and various musical experiments led to the formation of Gong Maison, which also featured Williamson.

Subsequently Allen and Smyth participated in numerous Gong reunions, including a 25th birthday celebration in London in 1994. This prompted the reformation of the “classic” Gong line-up which toured internationally from 1996 until 2001. Gong played two London shows in 2008, then released the album 2032 the following year. Allen, Smyth and their son Orlando all featured on the Gong album I See You (2014). Meanwhile Allen also pursued various other musical adventures, with The Magick Brothers, Acid Mothers Gong and the University of Errors.

He is survived by his sons.

Monday, 6 April 2015

Skirr Cottage Diary.

A good walk around Rudyard Lake. Heard at least ten chiff-chaffs whilst on route. I've a feeling they only made fall the day the before. On reaching home in Buxton heard one near the garden. Spotted a lone swallow over Rudyard, first of the year. Also saw two buzzards been mobbed by jackdaws, great crested grebes in breeding plumage, nuthatch, two oystercatchers. A bonus was good views of willow tit. Back at home a sparrowhawk nearly took my head off in the garden. Lots of buff-tailed queen bees taking advantage of the last flowers of the Viburnum Bodnantense.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)